Chapter 3 – Harnessing technology and new ways of working

Another way to increase the supply of financial advice in the UK is to increase capacity by embracing technology.

To be clear, we’re not talking about so-called robo advice here. No, we mean what’s sometimes called a bionic approach – augmenting the understanding and sensitivity of a skilled human with the efficiency and insights you get from using the right tech.

The case for embracing technology

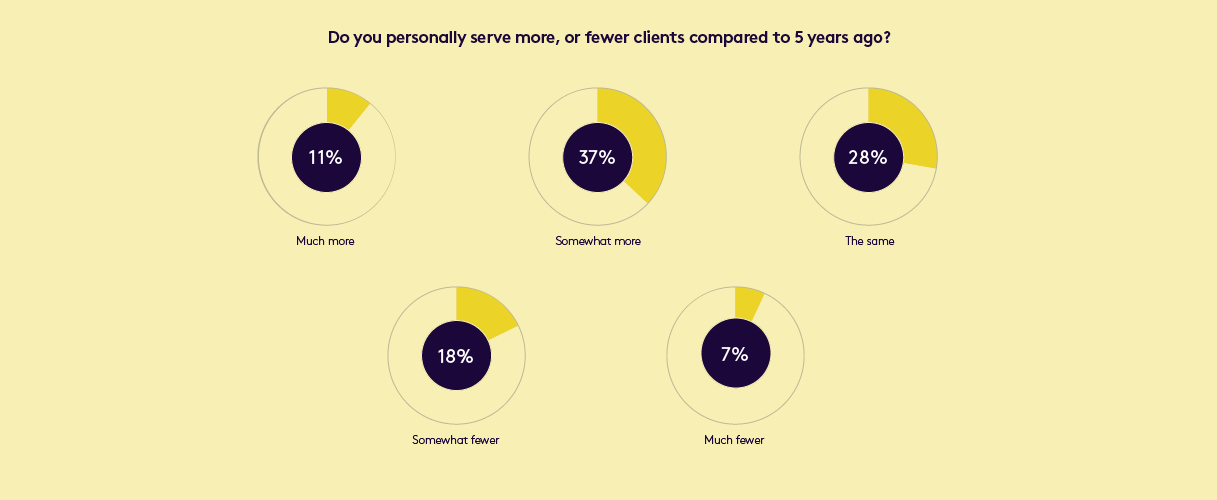

We asked advisers whether they are serving more or fewer clients today compared to five years ago. Here is what they said:

Encouragingly, just under half of all advisers appear to be serving more clients than they were five years ago. However, this is not a dynamic that can continue indefinitely. Closing the advice gap will require a step change in the industry’s capacity, one that can only be delivered by harnessing the power of new technological capabilities.

In addition, around a quarter of advisers say they are serving fewer clients than they were five years ago.

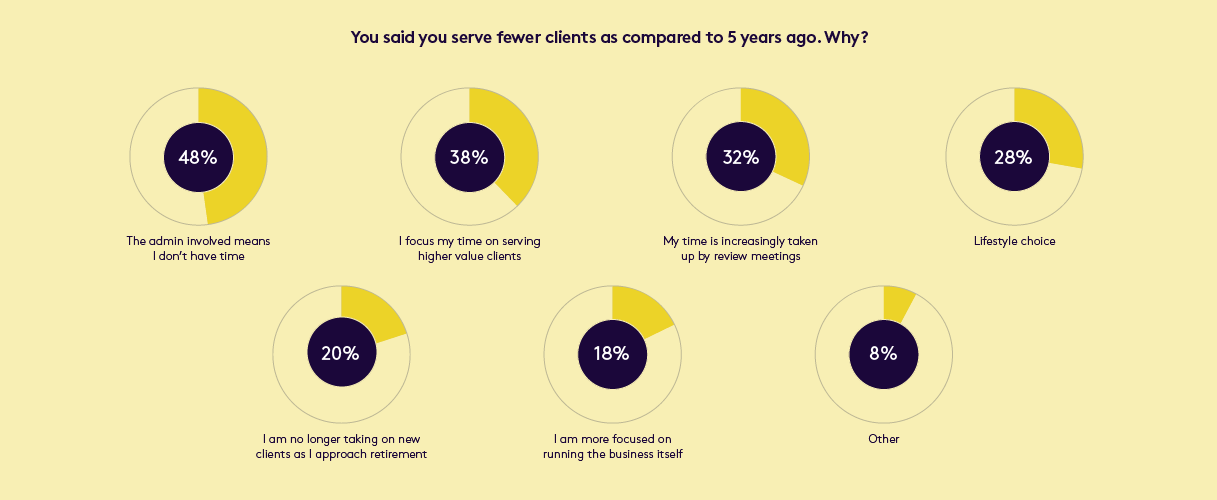

You might imagine this reflects the fact that many advisers expect to leave the profession in the next few years, and so are winding down their client banks in preparation for retirement. However, when we asked these advisers why it is that they serve fewer clients now than they did five years ago, the main reasons given were more prosaic:

“What I often hear is, we would love to serve more clients, but we can’t because of paperwork and red tape,” says Rohan Sivajoti, co-founder of NextGen Planners.

“If some of that were lifted, and we had better and more joined-up systems, with less re-keying, then I think advisers could serve more clients. As technology advances, I think this will change.”

Alan Marks, Managing Director at Harrison Spence, a London-based firm that specialises in buying and selling IFA businesses, suggests some firms may need to rethink their business model from the ground up.

“Really, advisers should be trying to differentiate their offering depending on the value of the client, typically in three tiers,” he says.

“Younger advisers increasingly understand this and are much more commercially astute. I really do see a phenomenally strong breed of advisers coming through in their 30s who are much more commercially minded. In the future I think we will see more service level agreements that are much more transparent about exactly what the client is getting.”

Glynn Jones, Group Development Director at advice firm LEBC, agrees that there’s an opportunity for firms to adapt their business models to try and serve more clients.

“I think the starting point is to understand your client base, and what their different needs are,” he says.

“So, what we’ve created are some bionic services which allow clients with simple needs to access services online so that the cost of advice and the time commitment required from them is proportionate to their needs.”

Currently, LEBC offers access to life and critical illness cover, wills and powers of attorney, mortgages and cash management through this bionic service.

“We have also developed a budgeting app to help customers take control of their day-to-day money without any pressure for them to buy a product or service from us,” says Jones.

“It’s about empowering consumers to make better use of their money and start the journey towards becoming investors who will in due course need a wider spectrum of advice.”

Does regulation need to change?

A term that is gaining traction is ‘guidance’, which refers to providing a service that doesn’t go as far as financial planning and financial advice, but which nevertheless could be of substantial value to many currently unserved potential clients.

“We should remember that not everyone needs ‘full fat’ financial planning,” says Sivajoti.

“Sometimes people just need an arm around the shoulder, telling them that they are doing the right thing. That’s where the development of light touch and guidance services could help an awful lot too.”

But could the current regulatory regime make it difficult for firms to offer this type of service?

“The difference between advice and guidance is whether you’ve gathered personal information from that individual and you are recommending a course of action based on that personal information, for example to invest in a specific product,” says James Priday, CEO and founder of P1 Investment Management.

“That’s the regulator’s stance, but I think that needs to change.”

A reappraisal of where the line is drawn between what is and is not regulated advice could free up advisers to provide lower cost services of genuine benefit to less wealthy clients whose financial needs are relatively uncomplicated.

Priday gives a hypothetical example.

“Someone asks me whether or not they should use £40,000 of inheritance to fill their ISA allowance across two tax years. On the call, I gather a bit of information and I learn they won’t need that cash until they are at least 55. So, I might recommend that they consider putting it into their existing pension instead.”

While this is likely to be a very short, very straightforward phone call, it would count as regulated advice. It would therefore need to be charged for accordingly, with the charges reflecting the costs of professional indemnity insurance and the administration that goes with providing regulated advice.

“In an ideal world,” says Priday, “I should be able to say that to someone without it being deemed as advice, even though I’m technically making a personal recommendation, requiring a suitability report. I could then charge a much lower fee for that type of service as I don’t have to do all of the things that need to be done when I am giving regulated advice.”

Scott Stevens, Head of Recruitment and Acquisitions at Quilter, makes a similar point about the economics of providing even light touch advice under the current regulatory regime.

“If you had someone with less than £100,000 of investable assets, they would struggle to find an adviser who’d want to service that,” he says.

“Because most of those financial advisers will charge between 0.5% and 1% as an advice fee. In order to make that worth their while, they want to earn between £1,000 and £2,000 a year from that client.”

However, the fixed costs involved in servicing a client aren’t diminished if the amount of investable assets is lower.

“The challenge is that if I’m now advising someone like this, and it’s only for a small amount of money, what about the annual suitability reports and all of the paperwork that’s surrounding this client? That’s a real problem to me. So that’s something we need to solve as an industry working with the regulator.”

The role of technology

In 2019 we asked financial advisers for their view on what the profession would look like in the future. 76% said they believed that a hybrid model would be the future, with 74% also saying that accessing financial advice online will become a key channel for younger clients to seek financial advice.

However, as Alan Marks at Harrison Spence points out, technology adoption has increased rapidly since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

“The speed of change has been enormous, and I think it would have taken between five and ten years in normal circumstances. The good advisory firms were already making good use of technology before the pandemic, and they saw a real boom during the lockdown, as their clients’ service was unaffected.”

This rapid change has been partly driven by the need to adapt, with advice firms adopting new technologies to ensure they can continue serving clients. However, coronavirus has also meant lots of clients are more engaged with technology themselves, and are now far more willing and able to conduct meetings over Zoom, for example.

Yet there remains a long way to go, argues Laura Russell, Head of Paraplanner Development at Succession Wealth.

“There needs to be wholesale investment in technology to help create efficiencies to make processes quicker and smoother,” she says.

“I honestly think that the companies that don’t invest in technology are not going to be able to survive. The ones who do well will be those that harness the potential of technology to help them meet the needs of all those clients and deliver the service they should be delivering to them.”

Russell adds that firms need to be thinking proactively about how they will need to adapt.

“We’ve got a group within Succession that is looking at the clients of the future and how they will differ from the average client we have today. We’re essentially asking ourselves questions about what we need to do, as a business, to move forward to meet those future needs and to be scalable and to operate effectively in the future. Because there is a marked difference between what the millennial generation wants and expects versus what lots of clients are used to getting today.”

How to put technology at the heart of your business

It’s one thing to get excited about technology’s potential to make the advice process paperless and much more efficient. But how do firms make this a reality?

“The first thing they need to do is process-map their business, so they are clear on all the different stages of client onboarding, their advice process and annual review process,” says James Priday at P1 Investment Management.

“A lot of firms don’t actually have that mapped out. It’s very ad hoc in many firms. You need to be able to show: this is how we do things; this is how we on-board a client; this is how we write a certain type of business, this is how we do an annual review.”

A process-map makes it much easier to see where technology can deliver the biggest benefits.

“Once you’ve got that,” says Priday, “you can start to ask, ‘How can I make these processes more efficient? How can I get all of the onboarding documents completed upfront with electronic signatures? How can I gather fact-finding data electronically?’ Then you want to look at how to integrate these individual processes with your back-office systems.”

What needs to change

In summary, this report identifies three areas where there is a significant opportunity to tackle the advice gap:

Raise awareness of financial advice as an attractive career option. Perception of the profession appears to be the main barrier to recruitment. That’s why it’s critical that we make more people aware, especially younger generations, that financial advice is an attractive career option, and highlight why it fits with what many people are looking for in a career.

Work with the regulator to enable a more flexible approach to providing advice and guidance. Many potential clients have relatively uncomplicated needs, and would benefits from some basic, low cost guidance from an expert. It should be possible for advisers to provide such services without fearing they’ll fall foul of the regulatory regime.

Serious investment in technology. Used in the right way, existing technologies can have a transformative effect, freeing up hours of time for advisers and their colleagues. Crucially, this lowers costs and enables advice firms to service more clients.

If you would like to read more detailed interviews with some of the contributors to this report, you can do so using the link below:

More Chapters

Introduction

The advice gap looks set to grow substantially – with significant implications for the financial advice profession.

Chapter 1 – Why the advice gap looks set to grow wider

Learn why the advice gap looks set to grow wider and why outdated perceptions of the profession are making recruitment more difficult.

Chapter 2 – Raising awareness of financial advice as a career

This chapter outlines how we can attract the next generation of talent as well as the significant commercial benefits of doing so.

Contributor profiles

Still want more? Here you can find extended conversations with some of the report’s contributors.

Related Insights

14 May 2020

Four ingredients to grow your business through professional connections

Hear from Strategic Partnerships Manager Charlotte Fairhurst on how to set yourself apart when establishing professional connections.

Want to find out more?

Contact us to find out more about our institutional offering.